King's Highway

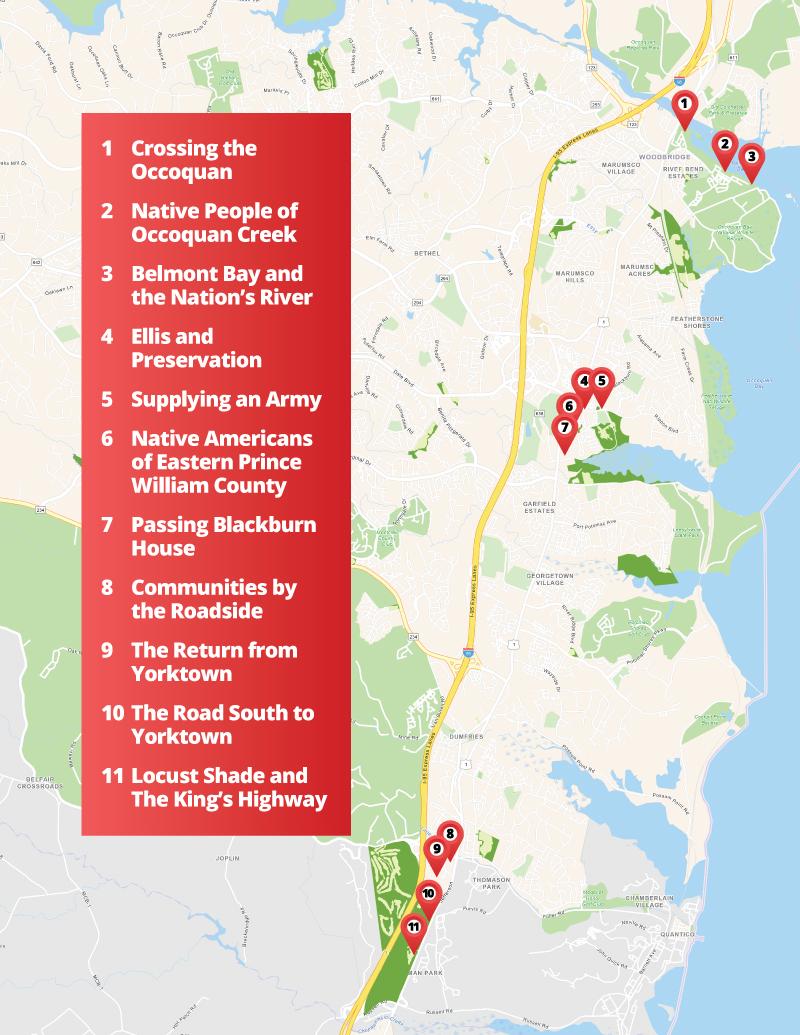

The King’s Highway is a connecting ribbon of history throughout eastern Prince William County. Native American paths grew into trails for early European settlers, then wagon traces, gravel roads, and paved highways. Near its modern descendant, US 1, you can still find the traces of many stories. The life and landscape of the native Doeg people. Civil War battles on land and river. Historic homes and communities, such as Rippon Lodge and Dumfries. Following the road itself retraces a frequent path of the Revolution years, carrying vital supplies to the victory at Yorktown, Generals Washington and Rochambeau, as well as our French allies north after the battle. The map below will introduce you to some of these fascinating places along the King’s Highway!

King's Highway Historic Site provides interesting locations for members of the community and visitors to enjoy a walk over the same ground travelled by humans for hundreds of years. Follow part of Washington's Army on its way to Yorktown, pass by one of the oldest homes in the county at Rippon Lodge, connect with area waterways, and find old trails where you least expect them at the National Museum of the Marine Corps.

King's Highway Historic Site is part of the Neabsco Regional Park. This park also includes the Neabsco Creek Boardwalk, Julie J. Metz Neabsco Creek Wetlands Preserve, and Rippon Lodge Historic Site. Click for more information on Neabsco Regional Park. The two county owned sites in Woodbridge are close to one another and Rippon Lodge Historic Site at the addresses below:

2201 Vantage Drive, Woodbridge, VA 22191

2114 Rippon Boulevard, Woodbridge, VA 22191

For questions or more information, please contact the Prince William Office of Historic Preservation at 703-792-4754 or [email protected].

.jpg) The Doeg and early English Settlement

The Doeg and early English Settlement

According to John Smith's account of his travels up the Potomac in 1609, he encountered various groups of Native American peoples. Among them were the Doeg, also known as the Dogue, Taux, and Tauxenent. In Prince William they lived on and named Chopawamsic, Quantico, Yosocomico (Powell's), Neabsco, and Marumsco Creeks. What Smith called their capital, Tauxenent, was located on the Occoquan at what is today known as Mason's Neck.

They were the first, or some of the first, to make a path along the Potomac shore. Water travel would have been the norm for most travel, but sometimes a runner would be quicker at carrying messages between the closely located settlements, and access to the interior of the county could be useful. The Doeg were forced from their homes, often violently to cross the Potomac and live in Maryland.

European settlers found these paths useful as well as settlement spread to the area through the 1660s and 1670s. Later, families such as the Brents, Scarletts, and Masons found these paths useful as well to connect their plantation holdings together. None would have accommodated a wagon or cart, and only some of them horses. Most land travel was on foot.

His Majesty's Business

It was difficult to deliver a letter in colonial British America. There was no mail system, people relied on hired couriers, travelers, and friends to carry messages to others. Going beyond a few miles might mean a voyage by ship, as roads varied from barely marked to bare dirt clearings, adding the risk of sinking to simply being lost. Business messages were habitually encoded to keep others from reading the contents.

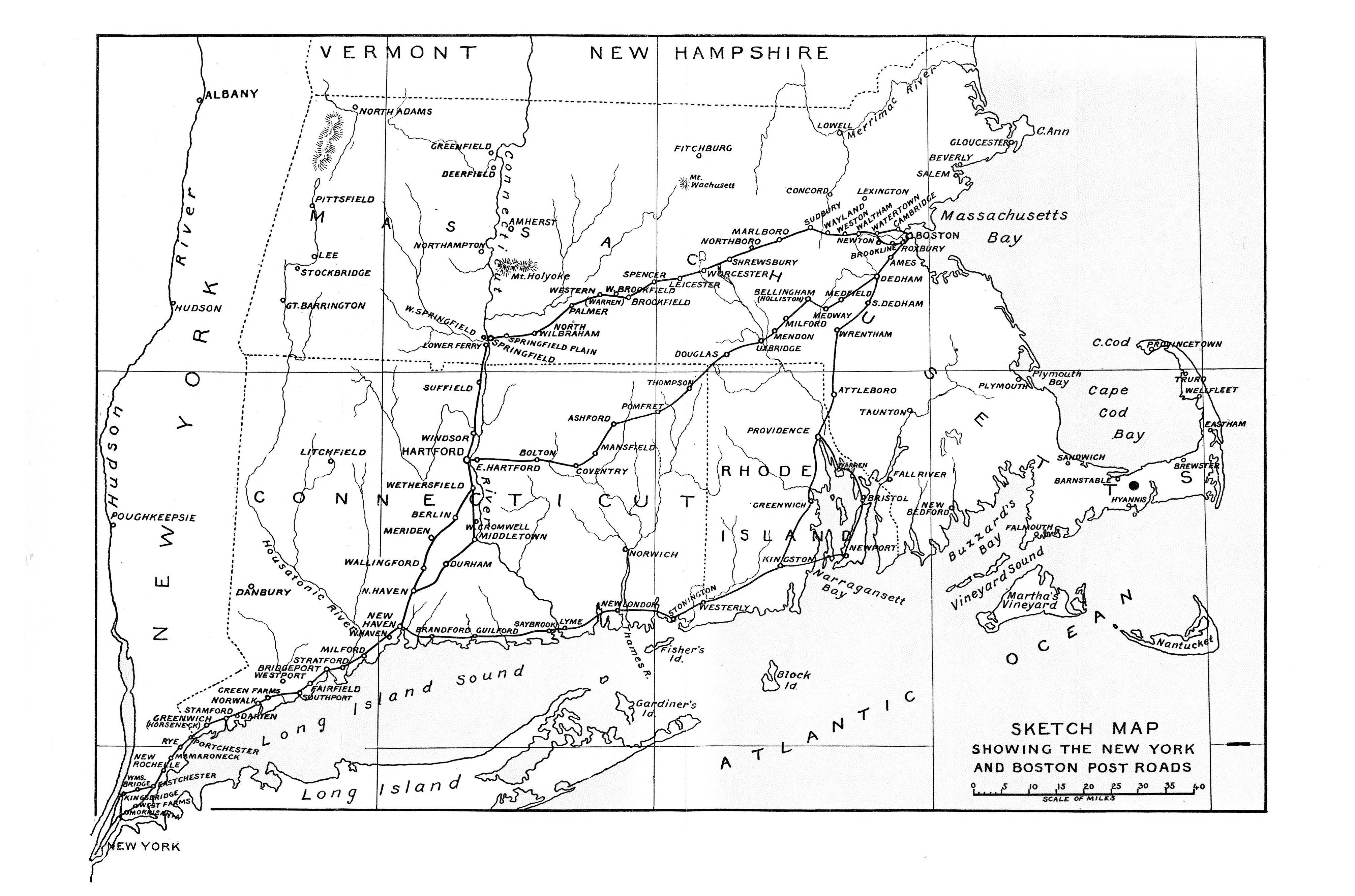

Hoping to remedy this, for official Crown business at least, King Charles II (reigned 1660-1685) ordered the governors of his Atlantic coast colonies to cooperate in building a road that would link all their capitals and as many local seats of government as possible. By the mid-1730s this roadway linked Boston with Charleston, SC. Entering Virginia through Alexandria, it hugged the coast down through Fairfax County and across the ferry at Colchester into Prince William. Here, the first county court house was ordered in built in 1731.

It passed by many local plantations, Deep Hole (Occoquan Bay NWR), Rippon Lodge, Leesylvania, Tayloe Iron Works, on the road to Dumfries. From there it followed the high ground as best it could through the swamps around Quantico and Chopawamsic creeks into Stafford County.

Revolution

War would drive the first major construction effort since it had been completed forty years earlier. Henry Lee of Leesylvania was ordered to call out county militia for a special project in a letter from George Washington; make passable roads from the Occoquan River ferries and fords to Stafford County, from the Fairfax to the Stafford County lines. Men, livestock, and tools were drafted for this important service. An Army was on the move.

Knowing that time would not allow the Continental Army and French "Expédition Particulière" to move between New York and Charles Cornwallis' British force at Yorktown in time for a trap to be sprung, most of the troops would go over water most of the way. However, artillery and supply wagons would have a much more difficult time going by ship. It was to aid this movement that Prince William men labored felling trees, digging out rocks, and other tasks to improve the rough path.

Lauzun's Hussars were the first to pass through Prince William, on September 17th. The last of the wagon trains crossed into Stafford County on the 29th. During their trip, the long supply trains camped at Marumsco Creek and in Dumfries, taking the better part of three days to make the journey through Prince William County.

Good Roads for Public Use

The road would change dramatically from the 1870s to the 1920s. Competition from river traffic declined, but most of it was picked up by a new challenger, the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad. Agitation for better roads would have to come from another angle.

Bicyclists were the first to push for "Good Roads" associations to pave and improve the roads. Their cause was picked up by farmers, businessmen, and auto travelers. This grass roots movement picked up speed and by 1906 the Commonwealth had a state highway commission. Court cases and legislation slowly established ways for the Federal government to fund interstate highways as well.

Focus was initially put on improving routes used to carry mail, agricultural commerce, or that would be important in the event of war. One of those routes was the Washington to Richmond Highway. Virginia had numbered this collection of dirt and gravel county roads "Route 1" in 1918. Nothing was settled just yet. Virginia Route 1 became Virginia Route 31 in 1923 and added the US Highway 1 name to its collection in 1926, then lost the VA-31 designation in 1933. At last it was One for good.

Realignment and Expansion: The Shirley Highway

Becoming US 1 changed the King's Highway forever. Changing needs, standards, and methods of transportation required a straighter road with better bridges. It was around the turn of the century the current walking paths were abandoned for new routes inland, roughly along the route US 1 follows today. Federal money built new bridges over Neabsco and Powell's Creek, while the RF&P donated the 1892 railroad bridge across the Occoquan for highway use in 1916.

This was of course not the end. Henry G. Shirley, Commissioner of the Virginia Department of Highways during the pivotal years from 1922 to 1941, did not want to build roads that would do for current use. The Department should plan and build roads that would suit future traffic. To that end, the plan was to bypass US 1's route from Woodbridge through Fairfax, Alexandria, and Arlington ending at the 14th Street Bridge. First called the Fort Belvoir Bypass, it would be a 17-mile, four-lane, limited access highway. The first in the state.

WWII heightened the need as new government workers and construction on the Pentagon increased traffic. Due to wartime material restrictions, only the four-mile stretch needed to reach the Pentagon was completed before the end of the war. From 1945 to 1952 the rest of the road, now named the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway was completed to Woodbridge. This was only the beginning. In 1964 I-95 was completed from Fredericksburg to the old end of the Shirley Highway, and from 1965 - 1975 it was upgraded to Interstate Highway standards. The modern route is still often altered today, to prepare it for future travelers.